The Girl With Her Back to the Crowd.

by norealplot

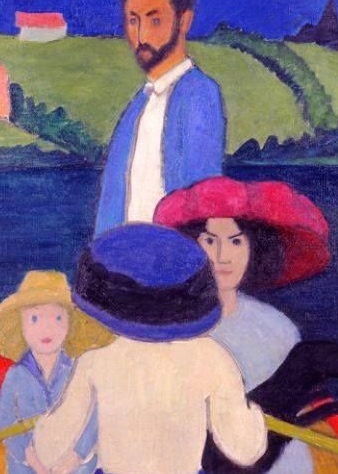

Boating, Gabriele Münter, 1909

Boating, Gabriele Münter, 1909

Devoted acolyte happily rows genius towards his glorious future. Right?

There’s a Kandinsky retrospective in town. More than a hundred paintings, drawings, and prints organized to show how Wassily Kandinsky evolved from a young Moscow law professor into the Father of 20th Century Expressionism.

It’s an impressive show, built around the disruptive-artist-hero story that Kandinsky liked to tell (not inaccurately) about himself, a St. George fearlessly slaying the dragon of traditional figurative art and modern materialist culture.

Improvisation III, Wassily Kandinsky, 1909

Improvisation III, Wassily Kandinsky, 1909

Most of the exhibited works come from the Pompidou Center in Paris, whose extensive Kandinsky collection was a gift from Nina Kandinsky, his widow and second wife. Or his third wife, depending on how you count it.

Which brings us to the girl rowing that boat.

She’s Gabriele Münter, the German-born daughter of a Jackson, Tennessee dentist and general-store owner, her father an immigrant who’d fled back to Westphalia to escape the American Civil War, leaving in-laws behind in Coffee Landing, Tennessee. Gabriele — or Ella (or Ellchen), as Kandinsky called her — was twenty-five years old in early 1902, when she joined a Munich art class taught by the 36-year-old, married Kandinsky.

Gabriele was looking for a serious art teacher. At that time, Germany’s formal art academies refused to admit women, for the most part, on the view that their biologically passive role of bearing and nurturing children meant they lacked men’s capacity for active artistic creativity. As one critic put it, quoting Goethe: “[S]ince woman cannot be original, she can only attach herself to men’s art. She is the imitatrix par excellence, the empathizer who sentimentalizes and disguises manly art forms . . . . ‘She is not capable of a single idea[.]’ . . . She is the born dilettante.” Women who tried serious art anyway? They became a bitter, de-feminized “third sex,” monstrous and unproductive, no good for babies and no good for art either.

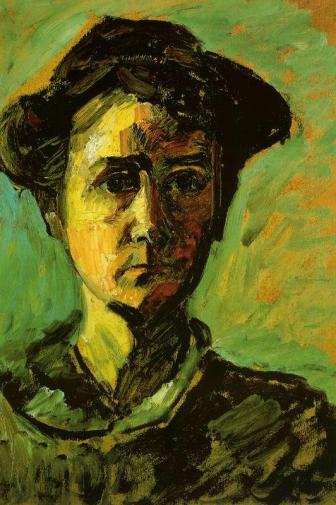

Self-Portrait, Gabriele Münter, 1908

Self-Portrait, Gabriele Münter, 1908

So women like Gabriele Münter ended up studying art privately, or in small informal studios, or in Ladies’ Academies that struggled to keep good teachers any longer than it took them to get jobs in the “real” art schools, teaching the men who’d become “real” artists. It was a disorganized, unsystematic, and frustrating way to learn. Thus, Gabriele was delighted to discover Kandinsky’s life drawing class in the Phalanx school he’d recently founded with a few other progressives. She later remembered, “[T]hat was a new artistic experience, how K., quite unlike the other teachers — painstakingly, comprehensively explained things and regarded me as a consciously striving person, capable of setting herself tasks and goals. This was something new for me, it impressed me.”

But Kandinsky began to press her for a more personal, romantic relationship, despite his marriage. By October of 1902, he could write, “I love you very much, and again a hundred times as much. You have to believe it and you musn’t forget it.” Still, he insisted, “When you come [visit him and his wife at home] on Monday don’t let it be apparent that we have seen each other more than twice. Yes? Once in school and once at your place yesterday.”

Gabriele, in turn, wrote Kandinsky (in a letter she did not mail):

My idea of happiness is a domesticity as cozy and harmonious as I could make it & someone who wholly & always belongs to me — but — it does not have to be that way at all — if it does not come about & if I do not find the right man — I am still very content & happy I intend now to find pleasure in work again . . . . At any rate I have always so despised & hated any kind of lying & secrecy that I just could not lend myself to it. If we cannot be friends in the eyes of the world I must do without entirely — I want no more than I can be open about & I want to be responsible for what I do — otherwise I am unhappy.

Interior (Still Life), Gabriele Münter, 1909 (Kandinsky in next room)

Interior (Still Life), Gabriele Münter, 1909 (Kandinsky in next room)

By the summer of 1903, Kandinsky’s wife had agreed in principle to divorce him, and he and Gabriele celebrated what he called their “engagement.” For the next roughly thirteen years — while he produced much of his most innovative and most famous Expressionist paintings, published his most influential theoretic manifestos, and organized his most well-known art movement, the Blue Rider — they lived and traveled together, a couple. As a couple, they developed their two prodigious bodies of work side by side.

And I mean two prodigious bodies of work. You already know his from Art History 101. The power of hers might surprise you.

Still Life, Yellow, Gabriele Münter, 1909

Still Life, Yellow, Gabriele Münter, 1909

Still, as Kandinsky became the increasingly prominent public figure, Gabriele’s status as his unmarried partner left her life confined and circumscribed in the conservative Munich society outside their small circle of artist friends. Even her own family, loving but solidly middle class, found it difficult to understand how she could live so intimately with this man. It was bad enough that he was not her husband, but, worse, he was still married to another woman.

Return from Shopping (In The Streetcar), Gabriele Münter, 1908/09

Return from Shopping (In The Streetcar), Gabriele Münter, 1908/09

In 1909, urged by Kandinsky, Gabriele bought a country house for them to share in Murnau, outside Munich. He’d still not pushed through his divorce, and in fact he spent the New Year holiday that year with his wife, writing Gabriele: “At the end of this coming year, you might not remain as lonely, as abandoned as has become the case now.”

Finally, we’re back to the boat.

In the summer of 1910, Gabriele Münter began to make preparatory studies for a portrait of herself rowing across Lake Staffel, near their Murnau villa. The figure of Kandinsky did not appear in sketches at first. But by the time she finished Boating, later that year, he’d taken up his dominant, standing position in the bow, like Washington crossing the Delaware. He stares down the viewer, electric blue eyes mirroring the mountains behind him and Münter’s ladylike hat low in the stern. She staunchly grasps the oars, single-handedly hauling him, their two idle guests, and a dog across the lake. Not only is her face turned away, her entire head is hidden, obscured beneath the demure, oversized hat. She and Kandinsky together form one strong, blue vertical beam. It’s a connection of color and direction, but not touch, nor shared viewpoint.

Both times I toured the exhibit here in Nashville, my guide made the same crisp claim: Gabriele Münter painted Boating to celebrate Kandinsky’s growing pre-eminence among the avant-garde, and to show how whole-heartedly she embraced her subordinate role as disciple and assistant, keeping his show on the road (or the lake, as it were). The catalogue calls her his “companion,” a “valued source of advice for the painter”; it notes she “compiled the first inventory of his works,” but says little else about her own work. “Münter’s hiding her face,” explained my guide. “She’s literally self-effacing.”

Both times I toured the exhibit here in Nashville, my guide made the same crisp claim: Gabriele Münter painted Boating to celebrate Kandinsky’s growing pre-eminence among the avant-garde, and to show how whole-heartedly she embraced her subordinate role as disciple and assistant, keeping his show on the road (or the lake, as it were). The catalogue calls her his “companion,” a “valued source of advice for the painter”; it notes she “compiled the first inventory of his works,” but says little else about her own work. “Münter’s hiding her face,” explained my guide. “She’s literally self-effacing.”

But I think that’s wishful thinking. Seeing Boating in person, hanging in the gallery near Kandinsky’s rushing blue horse, it struck me that Gabriele Münter’s maybe saying something else, something far harder for the hero-seeking art viewer to swallow. For maybe Boating‘s a portrait of the artist as a faceless, breaking heart.

Talk about Expressionism.

The year after Boating, Kandinsky traveled alone to Russia for an extended visit with his family and his old circle of friends, and the couple entered a period of prolonged separate travels, with shorter times together in between. They wrote letters, often daily, many of them fond and sometimes even passionate. They shared business concerns, a slippery gallery owner, a petty personal feud among artist friends. They made plans to reunite, and they discussed the house at Murnau. But Kandinsky’s tone cools, unmistakably, and Gabriele becomes increasingly pointed about his long-delayed promise to divorce his wife and marry her. They both allude to tension and trouble in their relationship during the previous year, 1910. He insisted they hire a housekeeper who’d once worked for him and his wife, a woman who disliked Gabriele and blamed her for the marriage’s disruption.

Still Life with Saint George, Gabriele Münter, 1911

Still Life with Saint George, Gabriele Münter, 1911

Revising and republishing his essays and manifestos for his growing audience, Kandinsky began to edit out complimentary references to Gabriele’s own work.

When World War I began in August 1914, Kandinsky raced back to his family in Russia, leaving Gabriele behind in Switzerland and Munich with instructions to dismantle their shared apartment and help his wife prepare to join him. Gabriele proposed they meet in Stockholm, hoping Kandinsky would call her onto St. Petersburg. She pressed Kandinsky to join her there, but he refused, saying he had no money to travel and feared being stranded outside Russia. In March 1915, he wrote,

Now I have been living alone . . and realize that this is the appropriate way of life for me. . . . I want to give my heart away and am incapable of doing it. . . . [P]erhaps I lack the ability. . . .This love, of which I speak, you have also never experienced and never had. That is why I tell you . . . that you never loved me. And life together as husband and wife without this love is a compromise with a greater or lesser aftertaste of a lie, that is, of sin. . . .You must never forget and must constantly feel that I, who ruined your life, actually am prepared to shed my blood for you.

In the summer of 1916, he promised again to travel to Stockholm that next December, to marry Gabriele soon after his fiftieth birthday.

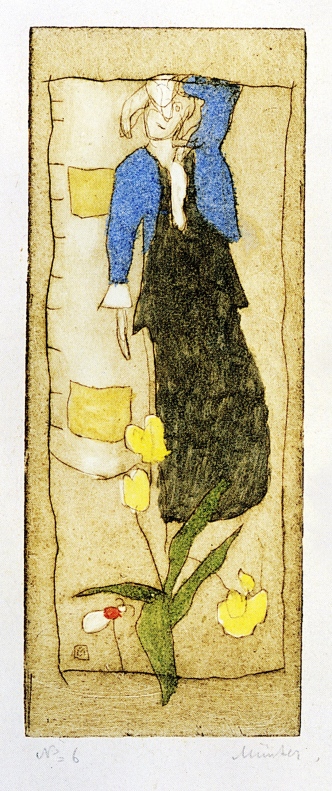

Woman Seeking, Gabriele Münter, 1916

Woman Seeking, Gabriele Münter, 1916

Instead, in February 1917, he married 17-year-old Nina von Andressvksaya. He did not inform Gabriele; he simply stopped answering her letters. He never told her he and Nina had a son, who died as a toddler in the chaos of Revolutionary Russia.

In 1921, finally, Kandinsky sent an agent to demand Gabriele return some paintings and other property she’d stored for him. He refused to communicate with her in person, and they never spoke again. But in 1922, he sent her a registered letter admitting that he’d “broken his promise to marry [her] legally,” accepting her as his “wife in conscience” (as she put it), and agreeing to a formal division of the disputed property, which took place in 1926. In the meantime, Gabriele struggled for money, seeking out portrait commissions and informal teaching jobs, and moving among friends’ houses and boarding houses.

As for Boating? It’s probably Gabriele Münter’s best-known work. She exhibited it herself, repeatedly, in Munich, Berlin, Paris, Zurich, Stockholm, and Copenhagen.

But not after 1919, when Kandinsky disappeared truly from her life.

An awfully traditional ending to this high-modernist tale.

***************

Sources: Reinhold Heller, Gabriele Münter: The Years of Expressionism 1903-1920 (Prestel-Verlag, 1997); Annegret Hoberg, Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter: Letters and Reminiscences 1902-1914 (Prestel-Verlag, 1994); Angela Lampe & Brady Roberts, Kandinsky: A Retrospective (Centre Pompidou, Paris, & Milwaukee Art Museum; Distributed by Yale University Press, 2014).

Laura- this was fabulous! I have always loved her work but embarrassingly didn’t know the extent of her relationship to that cad Kandinsky! A wonderful post and great images for a lunch time read!

Really lovely and sympathetic post about Gabriele Münter. Her paintings are astonishing even today and it is only thanks to her generosity we can study them and so many saved works by Kandinsky at the Lenbachhaus.